We originally published this post in November 2013 but it with the new season at our door it is highly relevant.

As highly enthusiastic mountain athletes there are many times we overextend our bodies to either achieve our goals or to simply have more fun. This can become a problem if we do it too often without balancing it with adequate recovery.

Overtraining can have serious long-term consequences on high level athletes. So if you are highly competitive, über-driven, or just training to push your limits then this article is for you!

Overtraining vs Overreaching

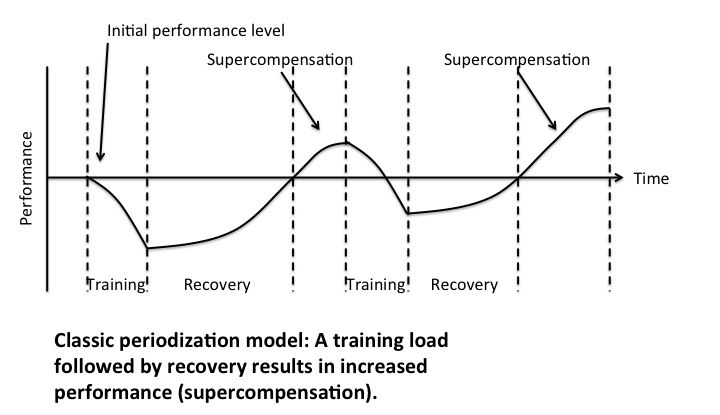

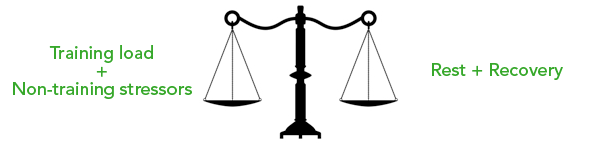

Increases in training load decrease performance capacity acutely, and it’s only with a sufficient rest and recovery that performance improvements occur.

Training load is a combination of the following:

- Exercise intensity (easy effort, hard effort… could be measured in heart-rate)

- Each workout’s length (in time)

- Workouts frequency (per day, week, month…)

What is overreaching?

The application of the training load is called overreaching. Functional overreaching (FO) is a temporary performance decrement in response to increased training load which will result in better performance after a period of recovery. This calculated process is also called super-compensation.

Functional overreaching is the cornerstone of modern periodization that follows an increasing load and recovery pattern.

What is overtraining?

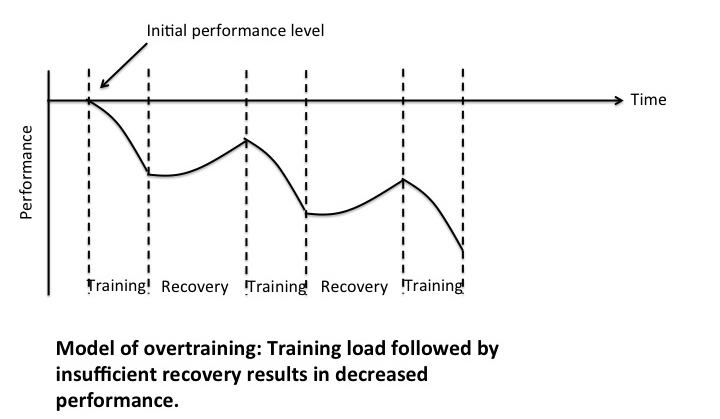

Excessive training without sufficient rest can lead to the physical and psychological impairment of ability called overtraining.

Non-functional overreaching (NFO) is manifested in a significantly longer or more severe decrement in performance. Physiological reductions in performance may be accompanied by psychological and neuroendocrine symptoms.

Because of the extended period of decreased performance, training time is lost and super-compensation does not occur.

Furthermore, chronic NFO can lead in rare cases to overtraining syndrome (OTS), with more extreme symptoms, and performance decrements lasting much longer. The specific differences between NFO and OTS are the subject of debate but sports professionals can agree that both have (possibly severe) negative effects on the athlete.

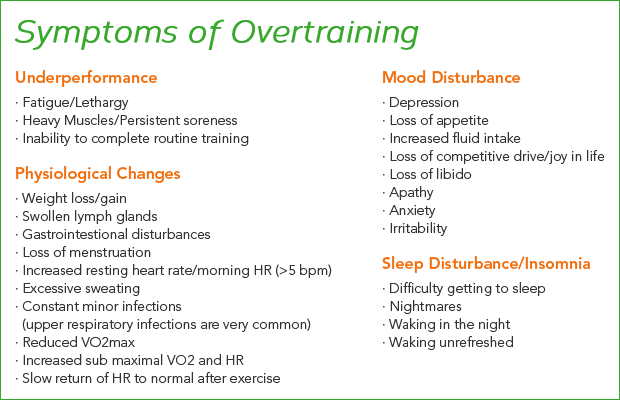

Symptoms of Overtraining

Overreaching and overtraining can present with a range of signs and symptoms that may be difficult to differentiate from infections or even functional overreaching preceding super-compensation (recovery).

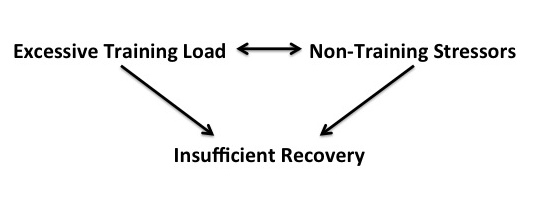

Causes of Overtraining

The cause of these symptoms is the result of three interacting factors:

- Heavy training load

- Insufficient rest

- Non-training physical or psychological stressors

The third factor – physical or psychological stressors – are common, especially in severe cases of OTS. These may be training related stressors or other life stressors, and may be recurring or more severe triggers. These include:

- Lack of training variation

- Insomnia

- Altitude training

- Work/family/relationship stress

- High stress competitions (playoffs)/excessive competition

- Illness

These causes are commonly associated with overtraining and can frequently be identified in hindsight by reviewing training logs. However, the specific pathophysiology that leads from poor recovery from training to overtraining is unclear.

The specifics of each hypothesis for overtraining is outside the scope of this article but it is likely a multi-factorial syndrome that includes inadequate fuel for muscle metabolism, high levels of oxidative stress, neural and hormonal depression, nervous system imbalance and chronic inflammation. These combine for a systematic effect on a range of organ systems.

Effects of Overtraining

The long-term effects of overtraining are varied and can potentially permanently change physical ability.

Like any overuse injury, extreme overtraining can lead to changes in tissue as a result of severe breakdown without recovery. Damage is unable to repair itself and muscle fibers are replace by fibrosis. Neurohormonal and metabolic effects can result in compromised nerve action on muscle tissues, decreases in the important hormones that regulate tissue repair, and severe fatigue.

Diagnosing Overtraining

Diagnosis of overtraining is difficult because no specific tests definitively identify overtraining; overtraining is a diagnosis of exclusion. Athletes with specific risk factors in whom all other possible diagnoses are ruled out may be overtrained. The diagnosis includes:

- A performance decrement lasting longer than usual (weeks to months) despite sufficient recovery

- Disturbances in mood

- No alternative diagnosis for decreased performance

Common differential diagnoses include asthma, iron deficiency, and malnutrition or disordered eating.

Overtraining cannot be diagnosed without a sufficient period of rest and recovery as this is a critical component of the definition. If the athlete returns to previous level of performance with 14-21 days of rest, a diagnosis of NFO can be made. If the required period of rest is greater than 21 days, OTS may be diagnosed.

A critical first step in diagnosing overtraining is a careful analysis of an athletes history. A nutrition history may reveal disordered eating. A complete blood count (CBC) will rule out iron deficiency. Analyzing recent training patterns may reveal increases in training load that could act as a trigger. Frequently, faced with recent poor performances, athletes will increase training load, triggering or exacerbating overtraining.

Consultation with a sports medicine physician can lead to further testing for other diseases or infections that may underly symptoms of fatigue. A referral to a sports psychologist is useful for assessing changes in mood. The profile of mood states (POMS) questionnaire is commonly used to diagnose and assess overtraining.

Treatment

Treatment of overtraining is highly dependent on the athlete. Rest is critical with some athletes requiring total abstinence from training while others recovering best with very small increases in volume from 5min/day to 1hr as long as fatigue is not limiting.

Intensity should be avoided completely until the athlete has recovered to their previous performance and motivation level. A sports physician and sports psychologist can provide significant support by monitoring progress

Prevention is Critical

Prevention is the most important message related to overtraining. Many mountain athletes compete for the joy of being outdoors and competing in the mountain environment. This can be both beneficial and increase the risk for overtraining.

Most mountain endeavours are dictated by the weather and rain is an excellent motivator for taking a rest day. Mountain athletes are also less likely to follow a strict training schedule and frequently train by feel, taking rest days when tired.

However, with the increasing competitiveness of mountain sports, athletes are training harder and more specifically for their sport to improve their performance.

The most important aspect of preventing overtraining is being aware of the causes and symptoms outlined above.

In order to increase training load and avoid overtraining, several simple principles of training can be employed:

- Training schedules should use some form of periodization to ensure adequate training load and recovery. This is augmented by proper preparation and tapering before competitions to ensure they do not act as a trigger for overtraining.

- Training loads should be adjusted based on fatigue during training, performance in competition and mood.

- If a training session was inordinately difficult, had severe weather stress or was impossible to complete due to fatigue, additional rest is advised.

- Even outside the context of overtraining, sufficient caloric intake and high quality nutrition with adequate hydration and sleep are a critical component for any athlete.

A coach is an extremely valuable asset for any athlete. Coaches can take an outside view of the training plan being followed without feeling the same pressures as an athlete to train and perform.

Physical testing, usually in the form of a standard time-trial is a highly effective form of monitoring for performance improvements or overtraining. A local loop or climb with defined start and finish can be used along with time, average HR, and perceived effort. By tracking these stats for your time-trial on a semi-regular basis, you can identify early signs of overtraining. That is, if you are under performing on your loop (going slow), working harder, or your average HR is high, it’s time to rest and start examining the rest of your training plan for overtraining risk factors.

Key points

To minimize the risk of overtraining keep in mind some simple yet key points:

- Overtraining can have serious long-term consequences on high level athletes.

- Reduced performance does not always mean that you are not training hard enough, frequently it means the opposite.

- Monitoring training, stress, and recovery are the best forms of prevention.

References:

- Kreher and Schwartz. Overtraining Syndrome: A Practical Guide (2012)

- Richard Budgett. Fatigue and underperformance in athletes: the overtraining syndrome (1998)

- Peter Janssen. Lactate Threshold Training (2001)

Stano Faban says

Hi Adam, great question! Here is my take on this:

I definitely believe that overtraining can happen more easily in a sport where most of the sessions are completed as a team, and probably much more easier in youth/junior categories. And that’s why it’s important for athletes to educated and monitor themselves.

About coaches:

If the coach is good then he/she should notice anything wrong with an individual whether part of a team or not. There are still lots sessions completed individually, outside of the team ones, therefore, if the coach is not paying attention to those then he/she is not good. But if the coach is good he will reduce the individual sessions in order to make sure the team ones are not suffering in quality/quantity.

Eric Carter says

Adam – I think that is a better question for a psychologist than physiologist. I guess Stano needs to hire more staff for SkinTrack 😉 In my experience though: In a team atmosphere yes, I think the odds of that are more likely. The article is written more in the vain of mountain athletes: skimo, climbing, ultra-running, and I think with these sports the coach-athlete relationship is slightly different. So to sum up – I’m not sure. Good question.

Adam Pellegrini says

Hey Eric,

Awesome article. I’m curious if there are ever disparities in how coaches perceive the risks of overtraining relative to the individual athletes. For example, a coach may be more likely to push their athletes towards some mean-field goal without particular concern for each individual athlete–some kind of “whatever it takes” mentality. I’d imagine that this is especially likely to happen in collegiate team athletics where the workouts are more tailored for the group (crew comes to mind) and there is less focus on the individual and more so on the group performance. It would be interesting to compare the frequency of overtraining in groups of D1 runners/nordic skiers vs. rowers as a first test.

Eric Carter says

Ryan – Thanks for reading! Aside from the guy’s exceptionally creepy picture, the MAF test seems to be just a different method of performance testing as I suggested in the article. Rather than running a set course and looking for changes in HR, he has you run at a specific HR and see if you run a different time. THe idea is the same but different outcome variable. Personally, I would prefer the timetrial style I suggested as it is more normal to what we are used to doing. If you try to maintain a certain HR as he suggests, you could be watching your HRM the entire time and not focusing on your effort. Also, doing a TT allows you to push hard on a course you enjoy once and a while. For me, it is a good reason to hammer a hard effort up The Chief. It is certainly a personal choice though.

Ryan says

Hi Eric:

Great article, what do you think about using a MAF style test each month to assess OTP? Here’s a link to this guy’s description: http://philmaffetone.com/maf-test (just ignore his creepy photo).