Announcement before a bigger announcement:

This article is a sample piece of content from a bigger project that is about to come from the SkinTrack “garage”. Since last summer, many pages have been written and videos have been filmed that we are excited to share!

We will let you know more details in the next couple of days but for now enjoy our insight into how you can go about planning your racing strategy and why it matters.

—–

The winter is around the corner, you have been training, so it’s time to talk about racing strategy. The single most important reason why you should approach your goal skimo races (or any races) with at least some kind of strategy is simple: training can take you far but not all the way. When the race day comes, strategy and tactics are what will help you to realize your full potential at the end.

Evaluating Your Strengths and Weaknesses

While training should be focused on honing both your strengths and weaknesses, racing is a different story. One of the key tactics is to take full advantage of your strengths. Going into race day, you should definitely have a good idea of what your strengths and weaknesses are from training and previous races. Identifying your strengths will help you make a plan and mentally prepare for some of the scenarios you may encounter. More experienced athletes might plan their entire season, including choosing races, around this concept.

Example: If your strengths are long, non-technical climbs then that’s where you could plan on making a difference and putting time into your competition. Alternatively, you may want to make a very hard effort on a section of course where you are weaker, knowing you will do the last flat climb fast no matter what..

Having a good understanding of where you currently stand is important. Keep in mind that all this is relative to the environment around you, i.e. your competition, race conditions, etc., because your strength in a local event might be just an average skill on a continental level.

Now, that we know where we suck and shine let’s look at the race day.

Race Course and Energy Needs Analysis

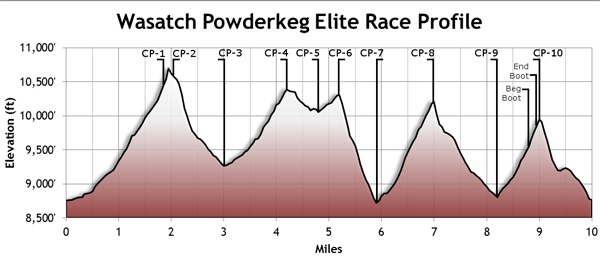

Race course analysis should be the cornerstone of building your racing strategy as well as your fuelling plan as both go hand-in-hand. Being proficient in race course analysis is one of the most important skills that can net you a lot of gain in exchange for little pain.

To create a great plan for a race, you should familiarize yourself with the course as much as possible. Also important is knowing the local climate and doing some research on the competition.

Analyzing the course

Ideally, you want to ski the full course before you race it. This is best accomplished over the course of several days leading up to the event unless it is a very short course that can be completed in less than 1.5 hrs at an easy pace.

If you cannot do a course recon ski, then study its profile and map provided by the organizer on their website or in the race package. Google Earth is an invaluable tool for ski mountaineers and should be used by racers in conjunction with the race map to get a good spatial understanding of the course.

The critically important stats are the elevation gain for each climb in the event and the nature of the descent. Distances are usually not that important in skimo racing but if a profile of a certain climb looks suspiciously flat then look into its distance as well.

Studying a topo map or Google Earth will also reveal the aspects of the slopes you will be going up and down. This is important because it can tell you whether a skin track might be icy or whether there might be a nasty sun crust on a particular descent.

Example: You are driving to a venue the night before and you never raced the course. It’s late March and you know there was a bluebird whole day after yesterday’s four inches of powder. The race starts at 8 am and you will be skiing down south facing slopes by 9 am. It’s a good chance they might be crusty.

Establishing your food plan to cover your energy needs

By answering couple of questions you can get this quite right every single time.

How long will it take me?

By studying the course profile, understanding the terrain involved, and knowing how much vertical you will have to climb, you can estimate the time it will take you to complete the course and even every part of it. With more practice you will get better at this.

Advanced racers should have a pretty good understanding of how quickly they can ascend during a race. By calculating your average vertical ascent rate in climbs from previous races, you should be able to calculate with some accuracy how long each climb should take.

Action step: When skiing or training at new places, try to estimate how long it will take you to get up new slopes whether you know their vertical or not.

How much fuel will I need?

Once you have calculated your total time for the race and for each climb, you can calculate how much food and fluid is needed. We will cover this in more detail further on but a rough guideline of 200-300 calories and 150-200ml water per hour is usually sufficient for a 1-3 hr skimo race in the cold. Be careful to maintain a good balance between fuel and fluid. Too much of either one can cause stomach issues.

Action step: During your training and practice races, test and note how much energy and water you need to consume over certain periods of time (1h, 2h, 3h…) to keep you going strong without causing upset stomach.

When and where should I eat?

This is very important! Start by figuring out how much you need to eat for each climb. Be sure to take into account the fact that most racers neglect nutrition towards the finish of the race when you are slowing down and need it most.

Second, determine where it would be the most convenient to take feeds. It is very likely that you will not be able to eat whenever you want. Plan on eating and drinking primarily during the non-technical parts of descents. Alternatively, do this at the very end of climbs (except on the first or last when the pace is commonly extreme). In both cases, your body will have some time to digest the food before it is needed in the subsequent effort. There are occasionally climbs that are split by a flat section where the pace relents, these may serve as good intermediate ‘feeds’ allowing a quick sip of energy or water. Regardless, feeding is primarily dictated by terrain and therefore, good course knowledge is key.

There is no set-in-stone formula for this. For each race you will need to juggle between the course profile/terrain and your energy needs before finding a satisfying solution for that specific day.

Action step: Enter a race (or do a practice race at your local hill with 3-4 climbs (1.5-2h) and descents over various terrain). Develop and try to stick to a fuelling plan. See how it works and tweak accordingly. You may have to balance calorie needs with the ability to take them in or stomach them. Ultimately, this is what you will be doing with each race under your belt.

Planning Your Racing Strategy

Planning a great racing strategy is a very delicate balancing act, never mind executing it. Because the plan will be based on your strengths & weaknesses, course analysis, energy needs, goals, and competition there are many variables to juggle. But don’t worry, the idea is not to have the perfect plan but rather to have a good understanding of what would be your ideal race scenario.

To borrow a quote from some great business gurus – “No business plan survives the first contact with a customer” – you should get used to the fact that adjustments will need to be made as the race goes on. Let’s take a look at how you can plan out your race strategy based on what you actually know.

Example 1:

Strengths & Weaknesses: You are great at short bursts of up to 5min up steep groomed climbs and mediocre on longer (20min+) non-technical climbs. You are not very good on technical ascents but you are a fast descender. You feel in good physical shape.

Course and Duration Analysis: About a minute off the line, a steep groomer leads to the top of first climb that you estimate will take you 25min. Non-technical descent follows. The next two climbs are around 15min over moderate non-technical terrain, and both are followed by technical descents. The last climb is a 40min slog with switch-backs, some moguls and a boot-pack at the end. The last descent is over technical terrain but conditions are nice and soft.

Goals and Competition: Based on assessing the current racing scene you want to finish top 20 in a stacked national field.

Example Race Strategy #1:

You should go hard off the gun, and as much of the first climb as possible, shooting for at least 15-16th place by the top. Ski hard on the first non-technical descent.

Mid-way through the second climb, you are going to evaluate whether you need to eat a gel or not. If yes, go ahead and eat it during the next couple of minutes. On this climb, you might also want to recover a bit after the first hard one. You push hard on the descent again.

On the third climb you will definitely want to eat a gel coming out of the transition if you didn’t do so on the previous one. You will put the hammer down again for this one. Then ski not to crash as this descent might be pushing your skills a bit.

On the last climb you are going to “feel into it”. Instead of trying to fight the elements as hard as you can, you will spend the first couple of minutes focusing on great technique and a nice breathing rhythm. Once you start to feel comfortable on the terrain, you start pushing harder but keep it sustainable. You will eat another gel around 10min into the climb. You finish the last 2-4min hard to position yourself behind someone, not more than 10-20 seconds ahead of you.

On the last descent, you will ski really hard if you have someone within your sight. If you don’t have someone less than 30 seconds in front of you, dial it back a notch to avoid crashing from skiing too fast. If someone is 10 seconds behind or in front of you then you must go for it like a mad man, win or crash, all or nothing.

Example Race Strategy #2:

You are going to go hard on the first 3 climbs, eating gels at the start of the 2nd and 3rd climb. Focus on technique and recovery the first 10min of the last climb. After that, see where you are energy wise. If you still have something left, pick up the pace a little. If not, then try to control the damage. Ski the first 3 descents not to crash (to recover after the hard efforts) and go for it all-out on the last one.

Example 2:

Let’s take the same race, same goals and competition but you have a different set of strengths and weaknesses.

Strengths & Weaknesses: You are skilled on steep and technical climbs but are not explosive. You have great stamina but are a weak skier. You feel in great shape.

Goals & Competition: If you want to be in top 20, that means you potentially need to beat our previous example skier. You anticipate you are in the same league (same potential for placing) as him from what you know about the two of you from previous races.

Suitable Race Strategy:

On the first climb you will ease into it, in order to find your day’s rhythm and not stress much about your competitors. By mid-way through the climb, you are picking up the pace and finishing strong, cresting around top 20. Then you ski hard despite your weaker descending skills – remember it’s not a technical descent.

On the second climb you are cruising hard, but cruising. Eat a gel 1-2min before the top transition. Ski not to crash – this is a technical descent.

You do the third climb the same as second, going hard but in control. Ski not to crash – it’s technical again.

At the beginning of the fourth, you eat a gel and bury yourself for the next 40min to hopefully pass your competitors and those others that passed you on the previous descents by the end of it. Then you ski like Bode Miller despite your limitations, thus, forcing your competitor to go beyond their skills as well.

Takeaway points

- To realize your full current potential you need to be aware of your strengths and weaknesses relative to your competition and the race course.

- Layout a fuelling plan first based on analyzing the course length and terrain (i.e.: acknowledge where it is possible to eat and where it is not)

- Analyse which parts suit you best in terms of terrain, where you would be able to gain a lot (aka make your move).

- Analyze where you will likely suffer, and determine whether it might make sense to fight it (if too technical part is only for few minutes of climbing) or you are better off using that part to recover.

- Merge and juggle the number 2, 3 and 4 to create one very ideal plan/scenario. Then a second one for when you are not feeling great on the first climb but you anticipate to come around by the second climb.

- Experiment, adjust and improvise. Sometimes take a fast start despite knowing you are not good at it. But hey, if the first climb is only 10-15min you have no choice anyway 😉

Personal example of race strategy planning

On January 5th, 2013 I lined up for the Jackson Hole, US Skimo Championship race, my first race that season.

Course & Duration analysis:

It was going to be a long race with almost 2500m of climbing and descending on all kinds of terrain. Starting at 2000m (6500f), highest point over 3000m (9850f)). It was going to be at least -20 C (-4 F) at the start line.

Strengths & Weaknesses (my conditioning at the time):

I had lots of mileage under my belt but lacked intensity as it was quite early in the season in regards to my goals. I was feeling strong on technical uphill terrain and felt comfortable to go the length. I felt confident for descents but was aware that I would have to pay extra attention as I hadn’t raced that course before.

Goals and Competition:

The field was stacked as ever. From previous Canadian results in this race (except for Reiner Thoni) it was clear that people as strong as I had a really hard time making it into the top 15. I attribute this to the fact that the Jackson Hole race course was simply too high altitude to properly race if you live between 0 and 400m (1300 feet). The goal was definitely to break top 15, with top 10 being the carrot. This was all given my conditioning, the competition and the altitude.

My race strategy:

My plan was to take it conservatively in the first 20 min then evaluate. This was mostly because of the altitude and my lack of intensity training. If I felt bad, I would just keep cruising until I would hopefully find my rhythm. Otherwise, try to push harder, but only on the technical parts (since that could benefit me more compared to others). Then, try to push on the second to last climb and see what the altitude does (most of the climb was above 2800m/9200f). I planned going full out on the last climb as I estimated it at around 15-20min and topping at only around 2400m (7900f). For downhills, I mostly planned on skiing not to get lost.

This is how it all came down:

After the first 20min, I didn’t feel my best so I eased off a bit. It was quite cold as well (-24 C / -11 F at the start line) so it was hard to judge whether it was the altitude or the cold, dry air. Once the technical skinning began and I started to find my rhythm. After a couple of technical climbs, I felt decent given the altitude. On the Corbet’s couloir climb (second to last), I pushed hard for the first 10min. Then lack of oxygen slowed me down and by the top I was pretty delirious. Fortunately, I had a really strong descent that was by far the longest in this race at around 1000m (3,300f) and it made a huge difference in my breathing. After a quick transition I was able to motor up the last, and very technical climb, passing about 6 people in the process. At the end I finished 13th, about 10 seconds behind the 11th guy. I took it as a good start to my season and a confirmation that my head was ready to analyze the races to come.

We hope that you have enjoyed reading the above and that it will help you race more strategically in the years to come.

And stay tuned for the bigger announcement via Facebook and Twitter 😉

Stano and Eric