I really had to pause when I read that there is a glacier in the Swiss Alps that has been receding by about 40m a year and also melting in thickness by around 6m a year. Such rapid glacier retreat is difficult to even imagine!

To understand effects of this fast melting on mountain adventures, and people living in the mountains, we reached out to our friend in Switzerland who studies glaciers and is a ski mountaineer himself.

Pascal Egli is a Swiss mountain runner, ski mountaineer and climber. He is the winner of the 2018 Sky Classic World Series and the Winner of The Rut Skyrun in Montana, USA in 2018.

Pascal is also an environmental engineer and an aspiring scientist, currently working on his PhD degree in glaciology and geomorphology at University of Lausanne, Switzerland.

Our interview is divided into two sections – the first one is about Pascal, and the second one and much longer talks about melting mountain glaciers.

About Pascal Egli

Q: Pascal, you have been in the mountains since young age. What do you like about being outside?

I like the fresh air, the sounds of nature and the feeling of freedom. Also, if you train your body, it can take you to amazing places in just a couple of minutes or hours.

Q: Where is your home and which mountains do you regularly visit?

I live in Leysin in the western Swiss Alps, between Lake Geneva and the Valais region.

Here, I can run up to 2400 m from my doorsteps, and of course, I also love to visit the 4000 m peaks of the Valais, about 2.5-3h away by train.

Q: You have been competing in mountain running for a long time. What kind of races do you enjoy?

I love two types of races. Those that are very wild, technical and in remote places that feel like an adventure, such as Tromsö Skyrace, Zermatt Ultraks Extreme Skyrace or Mount Elbrus race.

Then I love races with a wonderful atmosphere and with a high elite level, such as Zegama Aizkorri Marathon, Sierre-Zinal or Dolomyths Run.

» Pascal on Instagram

Some of Pascal best race results are:

- 3rd at Zermatt Ultraks Extreme, Switzerland (2020)

- Winner of Madrisa Trail 23k, Klosters/Switzerland (2020)

- Winner of the Sky Classic World Series 2018

- Winner of the Transvulcania VK, Spain (2018)

- Winner of The Rut Skyrun, Skyrunner World Series, Montana/USA (2018)

- 2nd at Giir di Mont 2017 (World Longdistance Mountainrunning Championships, Premana/Italy)

- 3rd at Mount Elbrus Skyrace, Russia (2016)

- 3rd at Dolomites Skyrace 2015

- Junior Swiss Champion in Mountainrunning (2007)

Interview about Melting Glaciers

Q: As a mountain athlete and an environmental engineer, you observe the impact of climate change in high mountains almost daily. Give us an idea of what you see and research.

Yes, I observe the impact of climate change on glaciers in three ways:

- Visually, observing conditions when I practice my sport.

- Through my work and measurements on glacier we have been studying here in Switzerland.

- When I read scientific publications about glacier recession in the Alps and worldwide.

For example, our measurements and observations of the Otemma Glacier, located in the southwestern Swiss Alps, show that it has been receding in length by approximately 40 m / year, and it has been melting in thickness by around 6 m / year.

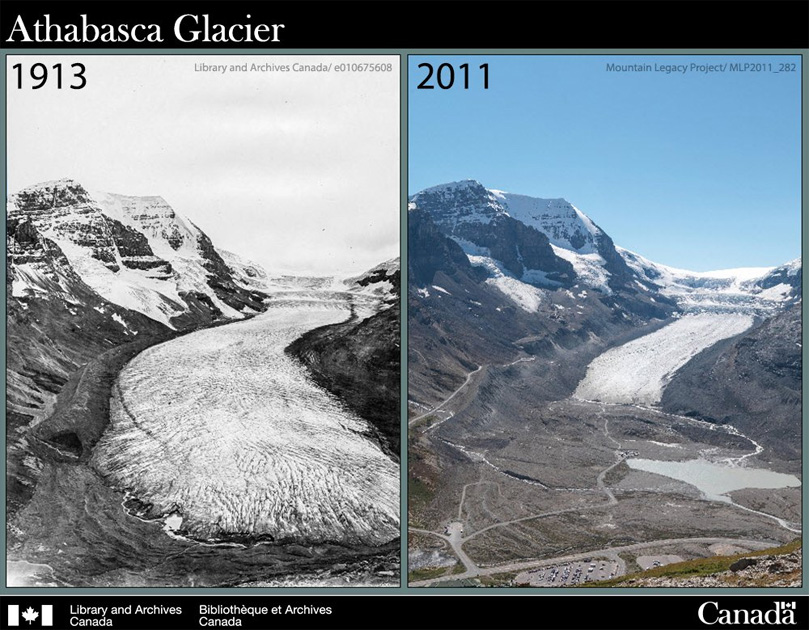

This glacier has retreated by 2.5 km in length since the 1960’s! We know this from historical aerial imagery. It was 9.5 km long in 1963 and now it is just about 7 km long. The projections say that the Otemma Glacier will be completely gone by 2070!

Q: What exactly do you focus on for your PhD research?

For my PhD, I am studying the geometry and dynamics of subglacial channels to better understand where and how the water flows underneath alpine glaciers, and how it can transport sediments.

This is important for understanding the hydrology (water cycle), ice dynamics of the glacier and sediment dynamics of alpine streams. Sediment content impacts hydropower lakes and dams, alpine streams ecology as well as natural hazards such as debris flows.

Q: Which other glaciers in the Alps are melting rapidly?

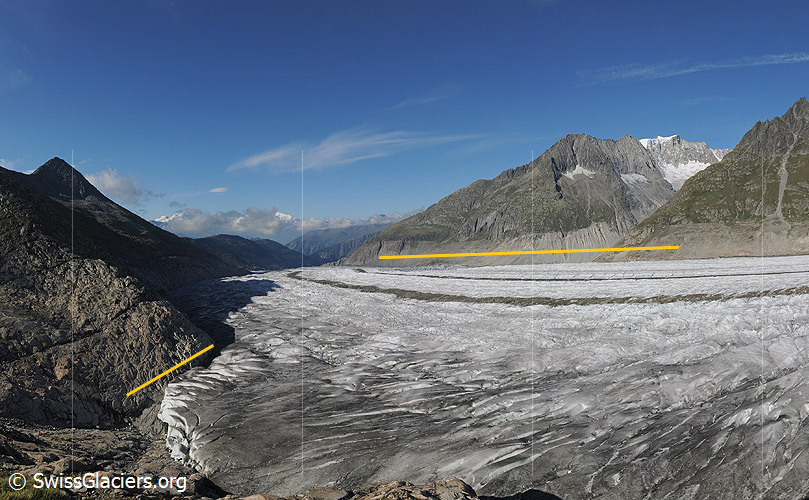

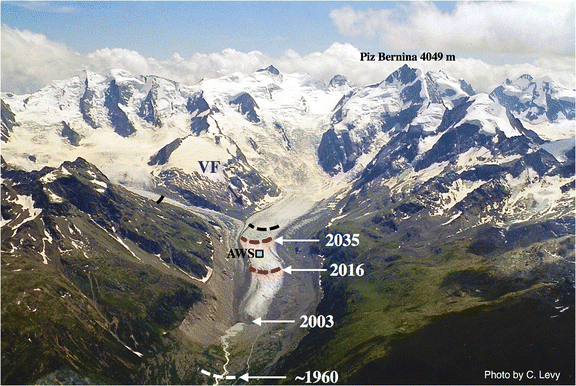

Here in Switzerland, the Morteratsch Glacier, the Aletsch Glacier, or the Gorner Glacier have all been receding at about 30-40 m in length per year.

But volume is the best indicator, so for example, the volume of the Morteratsch Glacier in 2000 was 1.1 cubic km and now in 2020 it is only about 0.75 cubic km3 – this is a loss of more than 30% in only 20 years! (Source: https://doc.rero.ch/record/324674 )

Q: What is the situation around the world? Or are there glaciers that are growing?

There are areas where glaciers are disappearing even faster than in the Alps, for example, the Peruvian Andes.

Glacier retreat in the Himalayas is similar to the Alps in general, but there are certain factors slowing down the retreat in some areas.

Here are two examples from the Himalayas:

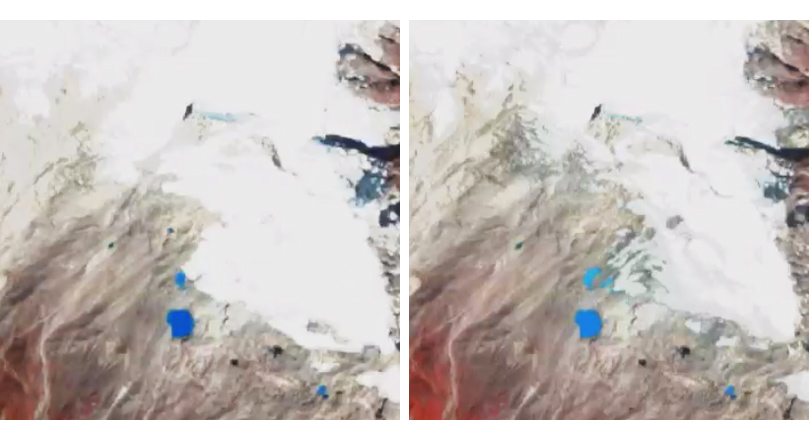

Rapid melting – I went to do fieldwork at Yala Glacier a couple of years ago. It is a small glacier at ‘lower’ altitude, reaching down to nearly 5000 m, in the Langtang Valley in Nepal. Between October 2016 and October 2020 it has retreated by dozens of meters, as it can be seen below from two satellite images in a tweet by Prof. W. Immmerzeel from Utrecht University.

Slow melting – Many glacier tongues in the Himalayas are covered by debris, which is rocks and sediment of up to 2 m in thickness. This debris cover acts as an insulation, therefore, slows down the melting process.

More information on debris covered glaciers worldwide can be found in this recent article by my friend Sam Herreid: https://samherreid.org/publication/global_featured/ ).

“Growing” glaciers:

Then some glaciers in southern Patagonia or in the Karakoram have been receiving larger amounts of precipitations in the last few decades. This has led to important snow accumulation in the upper part of the glaciers.

Despite rapid melt of the glacier tongues (in warm temperatures), the snow transformed into ‘new’ ice and it has been flowing down and partly compensated for the melt.

But even these glaciers are prone to recede because their glacier tongues are melting faster than the accumulation in the upper part is able to compensate for the melt.

Ice shields:

Another story are the great ice shields such as in Antarctica and Greenland where the melting has been very rapid. The speed of sea level rise is happening mainly depending on how fast these ice shields are melting.

Q: Due to melting glaciers, what are some of the new challenges for skiers and mountaineers?

Indeed, there are some really big challenges for skiers and mountaineers. Already now, some previously ‘classical’ alpine climbing routes are not doable anymore. There is an interesting paper about that – read here.

Another example of big impact of melting in the Alps is the famous gondola that goes from Chamonix to the spire Aguile du Midi. The permafrost and glaciers around its top station at 3,7777m are melting and it is highly likely that there will be negative consequences unless the rock the station stands will be somehow supported.

Then in the winter, the conditions for avalanches may change. For example, there is likely to be heavier snowfall due to a higher relative humidity in the atmosphere (a warmer atmosphere can take up more humidity), followed by sudden warming and consequently large wet snow avalanches.

But the main things we observe are:

- More difficult access onto glaciers due to steep & unstable moraines,

- larger crevasses with bad snow bridges (especially in late summer),

- larger bergschrunds that are sometimes impassable,

- collapse of entire rock pillars and of entire climbing routes,

- rockfall due to melting permafrost such as on Matterhorn, where in 2019 a guide and a client were killed because they were anchored on a block that detached and fell off with them.

Personally, I was shocked during our crossing of the famous ‘Haute Route’ from Chamonix to Zermatt in August 2017 to see how previously ‘easy’ glacier passages have become quite dangerous and difficult to pass, even for a rope team of three with considerable experience.

Q: How do fast melting mountain glaciers impact the lives of local people?

There are two or three factors to this story…

First, glaciers such as in the Alps since the 1950s have been melting rapidly and they have been contributing large amounts of water flowing into the hydropower lakes. This water is available mainly in spring and summer for electricity production, for public water needs downstream, for irrigation (farming!), for industry, and most importantly, for the alpine ecosystems.

The period (several years) of strongest melt when glaciers still have a considerable volume and melt rapidly is called ‘peak water’, and this period is already over for certain smaller glaciers in the Alps!

Even for the larger glaciers the ‘peak water’ period is soon ending.

After ‘peak water’ follows a period with declining water input during the summer months, because there is less ice left to melt – despite the higher summer temperatures we are now experiencing.

Now, with vanishing glaciers, the seasonality in water flow starts to increase. Most water is available just in the spring when snow melts. During summer, there is rainwater and a little ice melt. If there are longer drought periods this may be a serious threat to farming, industry and even public water supply (and partially also to hydropower).

Then, there are natural hazards as rapidly melting glaciers can cause glacier lake outburst floods, debris flows or serac/ice avalanches.

This regularly happens in the Himalayas where the glaciers are still bigger and people are less protected from floods and debris flows because there are no proper risk maps, insufficient emergency planning and very few civil engineering works (such as avalanche diversion dams) designed to protect people.

In the Alps, we can experience similar events, but it’s much easier as most valleys have hazard maps, safety concepts, continuous monitoring of the glaciers as well as protective measures such as avalanche retention/diversion dams.

Q: As a last question, in your opinion, how can we help the most to slow down the melting of glaciers in the mountains?

Most importantly, stay positive and tell people what they can improve (also to improve their own life quality!) instead of blaming them for something they are doing.

We cannot help the glaciers much right in the place where we live. Of course, some ski resorts put white blankets over the glaciers to reduce the reflectivity, therefore, make slowing down the melt in the summer. This works to some extent, but it is only temporary.

However, we can definitely do our part in many other ways. Here is a list of things we can change to affect climate change, therefore, also glacier retreat:

The big one, change your lifestyle to a less carbon and methane intensive one! For example, methane is a greenhouse gas 21 times more potent than CO2, and it is produced by activities such as cow and pig farming. Strive to eat much less meat and animal products in general. Eat organic and seasonal and local.

Buy less products in general and use public transport or a bike more often.

If your travel a lot as an athlete, mountaineer, or adventurer then for sure check out Outdoor Friendly Pledge by the Kilian Jornet Foundation. Its main goal is to target the pollution and greenhouse gases generated through outdoor sports.

One of the biggest impacts you can have as a person is to fly less. The Outdoor Friendly Pledge I already mentioned will help you how to do it more responsibly.

Besides that, I am also compensating my air travel by offsetting CO2-emissions. There are different options for this, ranging from cheap (and not always quite perfect, e.g. https://www.myclimate.org/ ) to expensive (and perfect, e.g. https://climeworks.com/ )

When you need to buy a new car (if your old one still works, then keep using it.), buy an electric instead of a gasoline car. The additional energy needed to produce an electric car and its battery is off set after a short time of driving this car.

If you own a home or even a house, a very effective measure to reduce your emissions is to insulate your home better and to invest in a heat pump for heating/cooling, to replace a pre-existing gas/petrol heating system.

Support modern and sustainable companies that are ready to change and to develop towards a low-carbon economy.

And last, but not least: advocate. Talk to your friends and family about it, without blaming anyone. Take political action, VOTE and/or try to influence politicians with letters and e-mails. Because to reduce our individual impact to a minimum, there will always remain considerable CO2-emissions due to the way our current economy works.

Sources

Modelling the retreat of Aletsch Glacier :

Jouvet, G., Huss, M., Funk, M., & Blatter, H. (2011). Modelling the retreat of Grosser Aletschgletscher, Switzerland, in a changing climate. Journal of Glaciology, 57(206), 1033-1045. https://doi.org/10.3189/002214311798843359

Modelling the retreat of Rhonegletscher :

Jouvet, G., Huss, M., Blatter, H., Picasso, M., & Rappaz, J. (2009). Numerical simulation of Rhonegletscher from 1874 to 2100. Journal of Computational Physics, 228(17), 6426-6439. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S002199910900285X

High Mountain Asia glacier mass balances :

Brun, F., Berthier, E., Wagnon, P. et al. A spatially resolved estimate of High Mountain Asia glacier mass balances from 2000 to 2016. Nature Geosci 10, 668–673 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2999

State of the world’s debris covered glaciers :

Herreid, S., Pellicciotti, F. The state of rock debris covering Earth’s glaciers. Nat. Geosci. 13, 621–627 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-020-0615-0

Asian water towers:

Immerzeel, W. W., Van Beek, L. P., & Bierkens, M. F. (2010). Climate change will affect the Asian water towers. Science, 328(5984), 1382-1385. https://science.sciencemag.org/content/328/5984/1382

Effect of climate change on water resources globally

Immerzeel, W. W., Lutz, A. F., Andrade, M., Bahl, A., Biemans, H., Bolch, T., … & Emmer, A. (2020). Importance and vulnerability of the world’s water towers. Nature, 577(7790), 364-369. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-019-1822-y

Sediment export and landscape change due to climate warming:

Lane, S. N., Bakker, M., Gabbud, C., Micheletti, N., & Saugy, J. N. (2017). Sediment export, transient landscape response and catchment-scale connectivity following rapid climate warming and Alpine glacier recession. Geomorphology, 277, 210-227. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169555X16300514

Effects on the alpine trail network:

Ritter, F., Fiebig, M., & Muhar, A. (2012). Impacts of global warming on mountaineering: A classification of phenomena affecting the alpine trail network. Mountain Research and Development, 32(1), 4-15. https://doi.org/10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-11-00036.1

Effects on mountaineering routes :

Mourey, J., Marcuzzi, M., Ravanel, L., & Pallandre, F. (2019). Effects of climate change on high Alpine mountain environments: Evolution of mountaineering routes in the Mont Blanc massif (Western Alps) over half a century. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research, 51(1), 176-189. https://doi.org/10.1080/15230430.2019.1612216

John Baldwin says

Great article Stano. Over the last 40 years I have seen huge changes in the glaciers all over the Coast Mountains in western Canada. For example the Bridge Glacier north of Whistler, BC has receded enough to create an 8km long lake at its snout that did not exist when I first skied across the glacier in 1980. And what’s even more astounding is the decrease in thickness of these glaciers. When comparing GPS readings of altitude to topographic maps that were made 40-50 years ago the difference can often be 150m.